Bash

- Awk

By Jake Pedersen|June 30, 2024

- The Bash Prompt

By Jake Pedersen|February 28, 2024

By Jake Pedersen|June 30, 2024

By Jake Pedersen|February 28, 2024

By Jake Pedersen|June 30, 2024

By Jake Pedersen|February 28, 2024

AWK is a powerful programming language designed for text processing and typically used as a data extraction and reporting tool. Named after its creators (Aho, Weinberger, and Kernighan), AWK is a versatile tool that can handle complex text-processing tasks with ease. In this post, we’ll explore three AWK commands, ranging from easy to advanced, using specific file contents and showing the output of each command. Let’s dive in!

Lets say the above file contains the following lines:

Name Age Occupation

Alice 30 Engineer

Bob 25 Designer

Carol 27 Teacher

awk '{print $1, $3}' data.txtName Occupation

Alice Engineer

Bob Designer

Carol Teacher

This simple command uses AWK to print the first and third columns of data.txt. The {print $1, $3} part of the command tells AWK to display the first and third fields (columns) for each line of the file. This is a great way to quickly extract specific information from a structured text file.

The above file contains the following lines:

Item Cost

Groceries 100

Utilities 150

Rent 1200

Transport 80

Entertain 200

awk 'NR > 1 {sum += $2} END {print "Total Expense:", sum}' expenses.txtTotal Expense: 1730

This command sums up the values in the second column of expenses.txt. The NR > 1 condition skips the header row. The sum += $2 part adds each value in the second column to the sum variable. Finally, END {print “Total Expense:”, sum} prints the total expense after processing all lines.

The above file contains the following paragraphs:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Vestibulum consectetur nunc sit amet risus varius, vel facilisis velit tincidunt.

Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas.

In quis luctus libero.

awk '{ if (length($0) > max) { max = length($0); longest = $0 } } END { print "Longest line:", longest }' paragraphs.txtLongest line: Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas.

This advanced command finds the longest line in paragraphs.txt. The length($0) function calculates the length of each line. The if (length($0) > max) condition checks if the current line is longer than the previously recorded maximum length. If it is, the max variable is updated to the current line’s length, and the longest variable stores the current line. After processing all lines, the END { print “Longest line:”, longest } block prints the longest line.

AWK is a powerful and flexible tool for text processing that can handle a wide range of tasks. From extracting specific columns to summing values and finding the longest line, AWK commands can be simple or complex, depending on your needs. These examples provide a glimpse into what AWK can do, but there’s much more to explore. Dive into AWK, and you’ll find it an invaluable tool in your text-processing toolkit!

Is your bash prompt so ugly it makes you sad? Well look no further, in this article I am going to show you how to make your prompt the envy of the neighborhood.

The Bash prompt is the command-line interface feature in Unix-like operating systems, it is provided by the Bash shell (Bourne Again SHell). The prompt is the area where the user types commands and interacts with the system. It typically appears as a string of characters followed by a cursor, signaling that the shell is ready to accept input.

The PS1 variable is what you use to create your primary prompt, this is the prompt most people think of and it is the prompt that lets the user know that the shell is ready to accept commands.

The PS2 variable is the secondary prompt, we won’t spend time on this, just be aware that it is the prompt that appears when the shell expects additional input to complete a command, for example when there is an unmatched parenthesis or quotation mark.

The PS3 variable is used with the select command, often used with a case statement. This is commonly used in the creation of menu scripts.

Lastly, the PS4 variable is used in conjunction with the xtrace, or -x, option and is displayed before each command is executed.

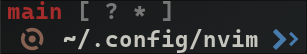

When you first install and open the Bash shell, the default prompt can be rather uninspiring, providing minimal information and lacking aesthetic appeal, it will most likely look something like this:

Fortunately, customizing the Bash prompt is a simple yet effective way to personalize your command-line experience. By incorporating different character sequences, you can not only enhance the visual appeal but also display relevant information that suits your preferences. In the following steps, I’ll guide you through the basics of customizing your Bash prompt and soon, you’ll find yourself navigating the command line with a tailored and visually pleasing prompt that suits your style and preferences, something similar to this:

To make changes to the prompt we need to use character sequences. Character sequences are used to change the appearance of your prompt, including color settings for text and background, and style settings for text including underline, bold, blinking, and bright

Before we begin, there are 2 character sequences you need to be aware of before you attempt to style your prompt and they are as follows:

\[and

\]These two sequences are important because they are used to enclose and indicate non-printing sequences. While these styling sequences are used to add color and style or other escape sequences to your prompt, they do not actually take up space on the command line so when you include these escape/style sequences without enclosing them in \[ and \], Bash may miscalculate the length of the prompt leading to misplacement of the cursor and this leads to character printing issues and other weird functional issues. By enclosing the non-printing sequences with \[ \] you tell the terminal to ignore these sequences when calculating the length of the prompt to ensure proper cursor placement and avoid unexpected behavior.

So take care to note in the following examples the escape sequences and the printed components of the prompts and which are wrapped and which are not.

Color is one customization you can use to create your ideal prompt, the following is a list of the color character codes, they are used in a sequence like this:

\[\e[32m\]| color | fg number | bg number |

|---|---|---|

| Black | 30 | 40 |

| White | 37 | 47 |

| Blue | 34 | 44 |

| Cyan | 36 | 46 |

| Green | 32 | 42 |

| Red | 31 | 41 |

| Yellow | 33 | 43 |

| Magenta | 35 | 45 |

So for example:

PS1="\[\e[31m\]This is red text\[\e[m\] " Will create a prompt that looks like this:

This text red text.

While:

PS1="\[\e[41m\]This is red background\[\e[m\] "Will create a prompt that looks like this:

This is red background

Text color is nice, but what if you want to dress it up a little more, you can add a little style with an underline, bright/bold colors, dim colors, blinking text, or reversed text using the following codes:

| style | number |

|---|---|

| normal | 0 |

| bold/bright | 1 |

| dim | 2 |

| underline | 4 |

| blinking | 5 |

| reversed | 7 |

Apply the style character your would lke to use as follows:

\[\e[4;32m\]So for example:

PS1="\[\e[4;32m\]This is green underlined text\[\e[m\] " will create a prompt that looks like this:

This is green underlined text

\[\e[1;32m\]So for example:

PS1="\[\e[1;32m\]This is bright green text\[\e[m\] "will create a prompt that looks like this: (depending on your terminal colors and settings)

This is bright green text

note the 4; or the 1; in the character sequenct, the 1; is for bright, the 4; is for underline.

Now that you know how to add color and style to your prompt, lets add the real important stuff, the stuff that gives you the needed information

about where you are, what you are, who you are, and more.

The following table is a list of charater sequences and the description of what they display:

| Character sequences | Displays |

|---|---|

| \a | The “alarm” character. Triggers a beep or a screen flash |

| \d | The current date, displayed in the format Weekday Month Date (e.g., Wednesday May 13). |

| \D{format} | The current date and time displayed according to format as interpreted by strftime. If format is omitted, \D{} displays current 12-hour A.M./P.M. time (e.g., 07:23:01 PM). |

| \e | An escape character (ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) 27) |

| \e[numberm | Denotes the beginning of a sequence to display in color. Number is a number, or pair of numbers, which specifies what color and style to use. See below for a list of colors and their number pairs. |

| \e[m | Denotes the end of a sequence to display in color. |

| \h | The hostname of the machine, up to the first “.” For instance, if the system’s hostname is myhost.mydomain, \h displays myhost |

| \H | The full hostname of the machine. |

| \j | Number of jobs being managed by the shell. |

| \l | The shell’s terminal device identifier, usually a single-digit number. |

| \n | A newline |

| \r | Carriage return |

| \s | The name of the shell (the basename of the process that initiated the current bash session). |

| \t | Current time displayed in 24-hour HH:MM:SS format (e.g., 19:23:01). |

| \T | Current time displayed in 12-hour HH:MM:SS format (eg. 07:23:01). |

| \@ | Current time displayed in 12-hour HH:MM:SS A.M./P.M. format (e.g., 07:23:01 P.M.). |

| \A | Current time in 24-hour HH:MM format, (e.g., 19:23). |

| \u | The username of the current user. |

| \v | Bash version number (e.g., 4.3). |

| \V | Bash version and patch number (e.g., 4.3.30). |

| \w | The current directory. The user’s home directory is abbreviated as a tilde ("~"). For example, /usr/bin, ~, or ~/documents |

| \W | The basename of the current working directory (e.g., bin, ~, or documents). |

| \! | The history number of the current command. |

| \# | The command number of the current command (command numbers are like history numbers, but they reset to zero when you start a new bash session). |

| \nnn | The ASCII character whose octal value is nnn. |

| \ | A backslash |

| \[ | Marks the beginning of any sequence of non-printing characters, such as terminal control codes. |

| \] | Marks the end of a non-printing sequence. |

So now that we have a nice list of the different characters you can use and what they will display, how do you use them? Well it is simple, say you want your prompt to show the name of the current user in white and the current working directory basename in red, that would look like this:

PS1="\u \[\e[31m\]\W\[\e[m\] "With this configuration, your prompt will look like this:

(I will use Jake as my user name, and home as the current dir)

Jake ~

Or say you don’t care about color and you just want to display the date, just do this:

PS1="\d : "This will display a prompt that looks like this:

Wednesday May 13 :

Now that we have a good idea of what character sequences do and how to use them the question becomes, where do we configure this? There are a couple of ways you can implement your own prompt. First, if you are just looking to change the prompt for the current session, you can just open your terminal, and enter the following:

bash-5.25: PS1="<enter your prompt configuration here>"This will change your prompt for the current session, but it will return to normal once you close your terminal. If you want to change it permanently, all you have to do is set the PS1 variable to whatever you like in either your .bash_profile, or in your .bashrc (you can use your .profile as well, if you prefer, but the other 2 files are more commonly used). Once set in one of the bash files, just close your terminal and reopen it or use the following command, and your prompt will be permanently set, at least set until your edti your PS1 variable again.

source%Now take your new knowledge and understanding of the PS1 variable and customize and configure to your hearts desire.